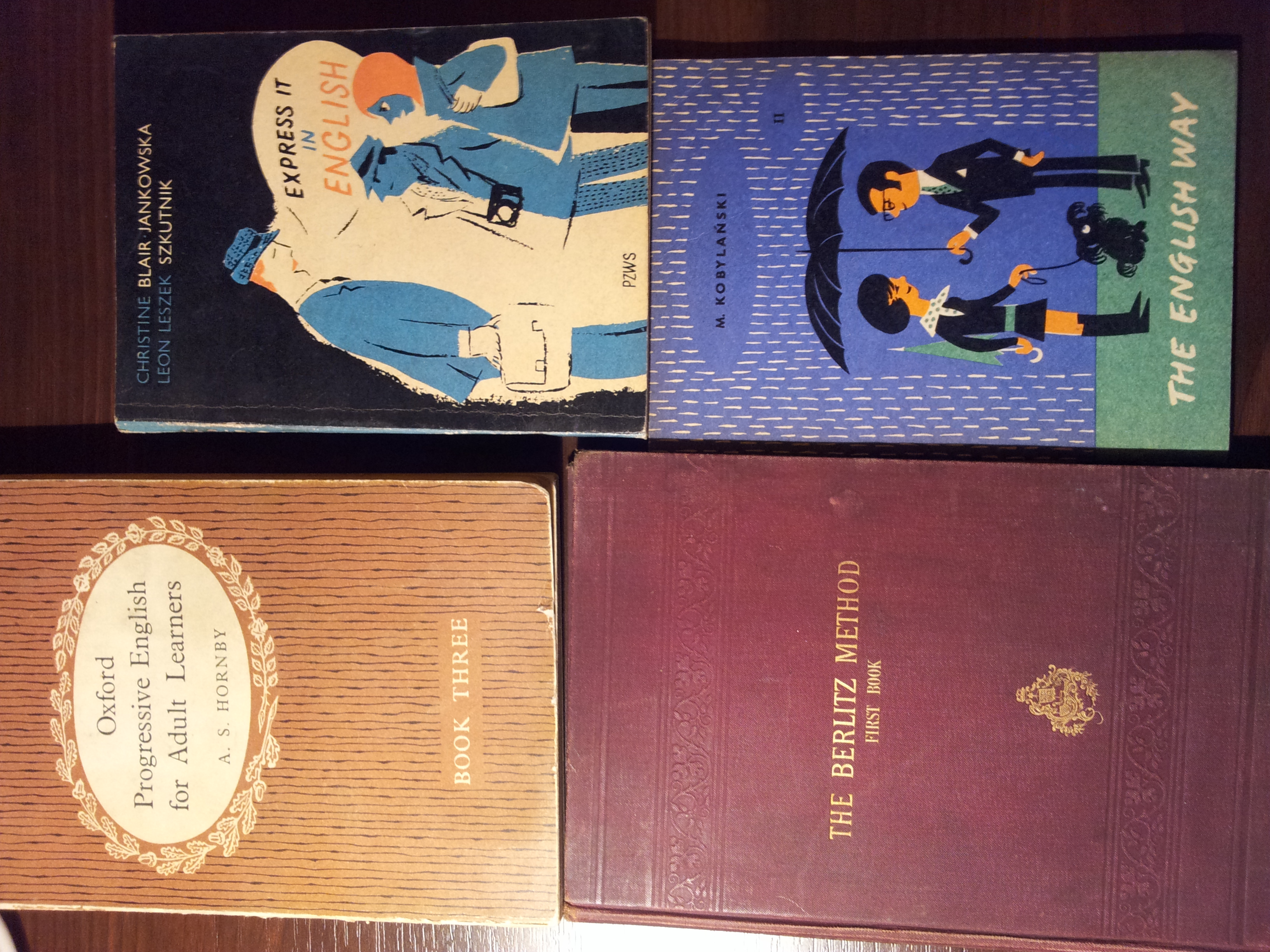

I took a while during my holiday to clean out my bookshelf. I found these four lovely old English readers / reference books. I’m sure that one day, I’ll write more about a couple of them, but today, I’m going to tell you one thing I learned from reviewing them quickly:

When it comes to language teaching methods, trust no one.

Follow me and I’ll explain. There’s good news at the end, I promise!

What is a language teaching method?

The easiest way to fail my teaching methodology course at the university was to get the “approach,” “method” and “technique” mixed up. They all sound like things you would do to your students, right? Well, not quite. Let’s spend a while looking at them – they’ll be useful in a moment when we decide why they matter to you as a language learner.

A language teaching approach is best described as a “philosophy” of teaching. This defines a set of beliefs or assumptions about what language is, how it’s learned / acquired and what role it plays in people’s lives. Basically, this is the “thinking stage” – research is carried out and interpreted, wise folks end up in rooms filled with papers and discuss about language (like on the clip below, but less funny). That’s approach.

A method – the thing we’ll focus on today – can be explained as “a systematic set of teaching practices,” based on a particular approach. In other words, after the thinking is done, it’s time for the planning stage – someone decides what they’re going to use in classrooms, how they’re going to explain things, what lessons will look like. The entire shape of a class, semester, the whole course – is planned in advance, and whilst some things are included, some others (which the approach considers “ineffective” or “not important” are left out.

All that’s left is to actually go and teach someone a language. That’s where the technique comes in. This is a real use of one of the practices planned by your teaching method. For example – if your language method allows you only to use the foreign language (and not your own), your teacher could go “shhh” every time you use your mother tongue. This is what can actually happen in a classroom – again, it’s based on what’s allowed by the method, which in turn relies on what the approach assumes to be right.

TL,DR: An approach = “We think language is / works / is learned like this…”

A method = “…so here’s how a good language class / course / textbook should look…”

A practice = “…therefore, Sally, go and do this, this and that today.”

What every language teaching method leaves out – a short list

- “The reason I want to learn is because…”

- “In five years’ time, I want to be able to…”

- “There’s this really nice Russian guy in the next office, and…”

- “I really hated my previous teacher – here’s what he did…”

- “Hey, I just found this, and I think I could use it!”

- “Why don’t we try something else today?”

- “My exam date got changed. It’s next month, actually.”

- “I’m fine for revision. I’ve got a system that really works.”

- “We’re doing a presentation in four weeks. Here’s what I need to learn.”

- “Sorry, I’ve had a rough day. I just don’t feel like doing any grammar this week.”

- “Well, what about you?”

- “Well, what about me?”

I’m sure you got the idea by now. With every language teaching approach/method/technique, the role of you as a learner is massively reduced. Your personal circumstances – motivation, learning preferences, history, or even the way you feel or the things you’re keen on at the moment – all this is not included.

Which is fair enough – how could it be? Teaching methods work on the broad perspectives and the general ideas. They won’t be able to respond to every learner’s needs, style or interests. This is okay, and teaching methods can still be immensely successful without that level of detail.

The problems begin when a language teaching method advertises itself with slogans like “results guaranteed” or “you’ll learn much faster than with method X.” That’s dangerous, potentially costly and definitely shady.

The problems also occur when language learners come into a language school without their own research and beliefs. This is how you can make sure you’re prepared.

Reverse research: your language learning method

Here’s what you’re NOT going to do: you won’t go out and buy every book about language learning. You won’t have to complete a PhD in applied linguistics – just so you can really benefit from your language classes. (It’s OK if you really want to – and I’d like to have coffee and a word with you if you do.)

What you COULD and SHOULD do, however, is reverse the process that is used on you as a language learner. In a classroom, what the teacher does (technique) should stem from planning (method) inspired by thinking and research (approach). The technique – what the teacher does – is where language teachers and learners meet.

The techniques is what you should react to. This is what you are able to judge: was this helpful or not? Is this the way I want to learn? Over time, if you look into your language classroom experience, you will have an opinion about quite a few of these techniques. This could go like this:

- – I’m terribly bored by listening to the coursebook CD, but motivated by listening to the news.

- – Reading aloud helps me remember words.

- – BUT when I’m reading for grammar, I’m tempted to ask my teacher to shut up and let me focus.

- – My test results show that I should do more spelling practice.

- – If my homework has so many punctuation errors, why don’t we work on this at all?

- – The role-plays were embarrassing at first, but now I’ve come to like them.

- – I appreciate that my teacher likes online resources, but after 8 hours spent staring at computer screens, I just can’t be bothered.

Get it? Here’s the funny part, in three uncomfortable facts:

- It is perfectly OK for these opinions to develop, and you’re entitled to have them, even though you’re not a language expert.

- 9 out of 10 language students keep these to themselves, summing them up with “…but hey, what do I know?”

- 9 out of 10 language teachers would love to hear these and change their classes so that you could learn the way you want.

Okay. So what can you do about it? As it turns out, there’s a lot to be done, if you go about it the right way. Here are some things to keep in mind:

Know yourself. It’s not about the method, the teacher, the other students. It’s your time, money and effort you’re investing. Wouldn’t you like to see how you’re doing? Keep a diary. Look over your test results. Go over the coursebooks or workbooks. Notice how you feel at your language class, and don’t dismiss these reactions.

Draw conclusions. Don’t be afraid to see the big picture emerging: it you consistently fail the listening parts of your tests, it’s okay to conclude that “I’ve got to figure out what’s going on here!” If you’ve got the evidence, and you’ve got the hunch, that’s enough to go by.

Share it if you can. See who you can speak to about the way you prefer to learn. Is your teacher okay with this kind of feedback? Is is possible to change the way things are? If not, is it something you can tolerate?

You’re in it for the long run. Chances are, you’ll enjoy speaking your new language your entire life. So you have a life’s worth of theories, opinions and preferences to develop. See how you’re getting on, observe the changes – and let your own learning philosophy grow.

Wiktor (Vic) Kostrzewski (MA, DELTA) is an author, translator, editor and project manage based in London. When he works, he thinks about languages, education, books, EdTech and teachers. When he doesn’t work, he probably trains for his next triathlon or drinks his next coffee.

BRAVE Learning (formerly known as 16 Kinds) is a lifelong learning and productivity blog. If you enjoy these posts, please check out one of my books and courses.

My recent publications, and my archive, is now all available on my new project: PUNK LEARNING. Hope to see you there!